Those who do not fit the norm, for whatever reason no matter how abusive, are outcasts.

In retrospect, societal norms throughout history have sometimes become fatally irresponsible. When it comes to popular movements and health trends, humanity has had its share of shameful events stamped forever into the history books. While working in Vienna General Hospital’s first obstetrical clinic, where doctors' wards had three times the mortality of midwives' wards, Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis proposed the novel idea of hand washing in 1847. Despite various publications of results where hand washing reduced mortality from 35% to below 1%, Semmelweis's observations conflicted with the established scientific and medical opinions of the time and his ideas were rejected. After his discovery, Semmelweis was committed to an insane asylum and promptly beaten to death by guards. As horrific as these visions and events can sometimes be, they continue to be played out in today’s society partially due to public ignorance, corruption, conflicts of interest and imbedded norms.

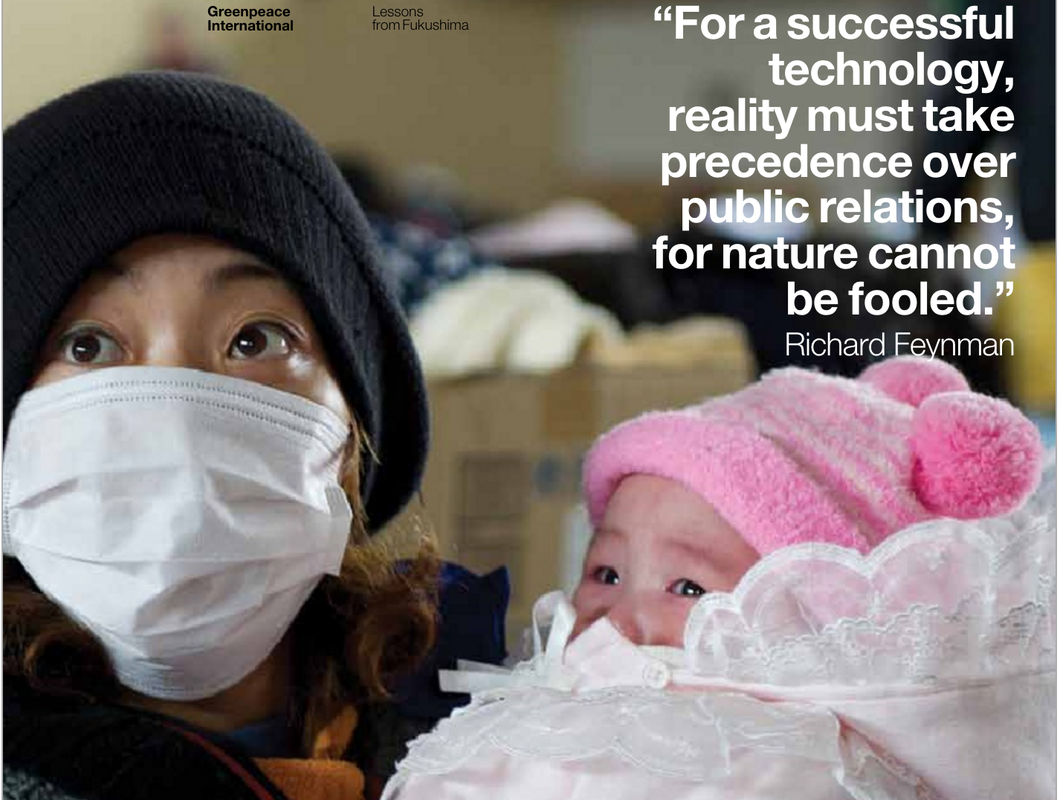

The world is rapidly approaching the five year anniversary of the worst nuclear disaster in human history. The triple meltdown at the Fukushima daiichi nuclear power plant has seen shameful omissions by global leaders and officials at every level. To compound matters, Japanese survivors are forced to submit to a complicit medical community bordering on anti-human. While the solutions to the widespread nuclear contamination are few, media blackouts, government directives and purposefully omitted medical reporting has made things exponentially worse. Over the last five years, the situation on the ground in Japan had deteriorated to shocking levels as abuse and trauma towards the survivors has become intolerable.

Even before the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan endured another nuclear disaster as a testing ground for the US military’s new nuclear arsenal on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The numbers of Japanese civilians killed were estimated at around 226,000, roughly half of the deaths occurred on the first day. After the initial detonation of the two nuclear bombs, both Japanese cities endured a legacy of radiation damage and human suffering for decades after. Tomiko Matsumoto, a resident of Hiroshima and survivor of the bombing described the abuse and trauma she endured by her society:

"I was shocked because I was discriminated against by Hiroshima people. We lived together in the same place and Hiroshima people know what happened but they discriminated against each other. ..I was shocked.”

"There were so many different kinds of discrimination. People said that girls who survived the bomb shouldn't get married. Also they refused to hire the survivors, not only because of the scars, but because they were so weak. Survivors did not have 100 percent energy.”

"There was a survivor's certificate and medical treatment was free. But the other people were jealous. Jealous people, mentally discriminated. So, I didn't want to show the health book sometimes, so I paid. Some of the people, even though they had the health book, were afraid of discrimination, so they didn't even apply for the health book. They thought discrimination was worse than paying for health care.”

A similar scene is playing out today in Japan as residents of the Fukushima prefecture, who survived triple nuclear meltdowns, are forced to endure similar conditions over half a century later. Fairewinds Energy Education director and former nuclear executive Arnie Gundersen is currently embarked on a speaking tour of Japan as their population continues to search for the truth about nuclear risks and the reality of life in affected areas of Japan after the 2011 disaster. Many Fukushima prefecture residents are still displaced and living in resettlement communities as their city sits as a radioactive ghost town. Visiting one such resettlement community, Gundersen had this to say:

“Today I went to a resettlement community. There were 22 women who met us, out of 66 families who live in this resettlement community. They stood up and said my name is…and I’m in 6A…my name is…and I’m in 11B and that’s how they define themselves by the little cubicle they live in — it’s very sad.”

Speaking with the unofficial, interim mayor of the resettlement community, she told Gundersen

“After the disaster at Fukushima, her hair fell out, she got a bloody nose and her body was speckled with hives and boils and the doctor told her it was stress…and she believes him. It was absolutely amazing. We explained to her that those area all symptoms of radiation [poisoning] and she should have that looked into. She really felt her doctor had her best interests at heart and she was not going to pursue it.”

Speaking about how Japanese officials handled this resettlement community’s (and others?) health education after the disaster, Gundersen reported:

“They [the 22 women who met with Gunderson] told us that we were the first people in five years to come to them and talk to them about radiation. They had nobody in five years of their exile had ever talked to them about radiation before…Which was another terribly sad moment.”

When asked if the women felt isolated from the rest of Japan they described to Gundersen the following:

“Some of them had changed their license plates so that they’re not in Fukushima anymore — so their license plates show they’re from another location. When they drive back into Fukushima, people realize that they’re natives and deliberately scratch their cars…deliberately scratch their cars because they are traitors. Then we had the opposite hold true that the people that didn’t change their plates and when they left Fukushima and went to other areas, people deliberately scratched their cars because they were from Fukushima.”

Gundersen summed up the information he received by saying, “The pubic’s animosity is directed toward the people of Fukushima Prefecture as if they somehow caused the nuclear disaster.”

In retrospect, societal norms throughout history have sometimes become fatally irresponsible. When it comes to popular movements and health trends, humanity has had its share of shameful events stamped forever into the history books. While working in Vienna General Hospital’s first obstetrical clinic, where doctors' wards had three times the mortality of midwives' wards, Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis proposed the novel idea of hand washing in 1847. Despite various publications of results where hand washing reduced mortality from 35% to below 1%, Semmelweis's observations conflicted with the established scientific and medical opinions of the time and his ideas were rejected. After his discovery, Semmelweis was committed to an insane asylum and promptly beaten to death by guards. As horrific as these visions and events can sometimes be, they continue to be played out in today’s society partially due to public ignorance, corruption, conflicts of interest and imbedded norms.

The world is rapidly approaching the five year anniversary of the worst nuclear disaster in human history. The triple meltdown at the Fukushima daiichi nuclear power plant has seen shameful omissions by global leaders and officials at every level. To compound matters, Japanese survivors are forced to submit to a complicit medical community bordering on anti-human. While the solutions to the widespread nuclear contamination are few, media blackouts, government directives and purposefully omitted medical reporting has made things exponentially worse. Over the last five years, the situation on the ground in Japan had deteriorated to shocking levels as abuse and trauma towards the survivors has become intolerable.

Even before the nuclear disaster in Fukushima, Japan endured another nuclear disaster as a testing ground for the US military’s new nuclear arsenal on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The numbers of Japanese civilians killed were estimated at around 226,000, roughly half of the deaths occurred on the first day. After the initial detonation of the two nuclear bombs, both Japanese cities endured a legacy of radiation damage and human suffering for decades after. Tomiko Matsumoto, a resident of Hiroshima and survivor of the bombing described the abuse and trauma she endured by her society:

"I was shocked because I was discriminated against by Hiroshima people. We lived together in the same place and Hiroshima people know what happened but they discriminated against each other. ..I was shocked.”

"There were so many different kinds of discrimination. People said that girls who survived the bomb shouldn't get married. Also they refused to hire the survivors, not only because of the scars, but because they were so weak. Survivors did not have 100 percent energy.”

"There was a survivor's certificate and medical treatment was free. But the other people were jealous. Jealous people, mentally discriminated. So, I didn't want to show the health book sometimes, so I paid. Some of the people, even though they had the health book, were afraid of discrimination, so they didn't even apply for the health book. They thought discrimination was worse than paying for health care.”

A similar scene is playing out today in Japan as residents of the Fukushima prefecture, who survived triple nuclear meltdowns, are forced to endure similar conditions over half a century later. Fairewinds Energy Education director and former nuclear executive Arnie Gundersen is currently embarked on a speaking tour of Japan as their population continues to search for the truth about nuclear risks and the reality of life in affected areas of Japan after the 2011 disaster. Many Fukushima prefecture residents are still displaced and living in resettlement communities as their city sits as a radioactive ghost town. Visiting one such resettlement community, Gundersen had this to say:

“Today I went to a resettlement community. There were 22 women who met us, out of 66 families who live in this resettlement community. They stood up and said my name is…and I’m in 6A…my name is…and I’m in 11B and that’s how they define themselves by the little cubicle they live in — it’s very sad.”

Speaking with the unofficial, interim mayor of the resettlement community, she told Gundersen

“After the disaster at Fukushima, her hair fell out, she got a bloody nose and her body was speckled with hives and boils and the doctor told her it was stress…and she believes him. It was absolutely amazing. We explained to her that those area all symptoms of radiation [poisoning] and she should have that looked into. She really felt her doctor had her best interests at heart and she was not going to pursue it.”

Speaking about how Japanese officials handled this resettlement community’s (and others?) health education after the disaster, Gundersen reported:

“They [the 22 women who met with Gunderson] told us that we were the first people in five years to come to them and talk to them about radiation. They had nobody in five years of their exile had ever talked to them about radiation before…Which was another terribly sad moment.”

When asked if the women felt isolated from the rest of Japan they described to Gundersen the following:

“Some of them had changed their license plates so that they’re not in Fukushima anymore — so their license plates show they’re from another location. When they drive back into Fukushima, people realize that they’re natives and deliberately scratch their cars…deliberately scratch their cars because they are traitors. Then we had the opposite hold true that the people that didn’t change their plates and when they left Fukushima and went to other areas, people deliberately scratched their cars because they were from Fukushima.”

Gundersen summed up the information he received by saying, “The pubic’s animosity is directed toward the people of Fukushima Prefecture as if they somehow caused the nuclear disaster.”

When it comes to health decisions, the medical community and political class has polarized the conversation into an “either-or” “us vs. them” mentality. Reckless lawmaking and biased reported has only driven the Japanese public further down this slippery slope. In many countries, the public watched as medical dogma and ideology captured healthcare, which in turn began to direct policy and law. Many societies beyond Japan are now facing difficult choices as the free expression of health preservation and medical choice has fallen into a dangerous grey area. Oscillating between authoritative legal action, medical discrimination and public abuse, society’s norms appear to be rapidly heading down the wrong road. Untold damage and traumas are unfolding as governments hide information and quietly omit vital data further fueling the fire. Alternative media and the work of those in medicine with true integrity and compassion have herculean tasks awaiting them as they work to change a historically dangerous narrative attempting to root.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed